One of the advantages of posting your ideas to your own journal, blog, or ePortfolio on an ongoing and long-term basis is that you can go back and evaluate and analyze your thinking and then continue to refine and synthesize your ideas. As new data or information comes to light or your research confirms or contradicts your hypothesis you can update your synthesis. The following is a synthesis from the post How to Change the World One Learner at a Time from January 2021 which is an update to a 2015 post Changing the world, one learner at a time as well as many other ideas that I have posted over the years. The higher-order thinking that I referred to in the Owning Your Learning Process video above is also a key function of the Learner’s Mindset which is achieved by a change in thinking about learning, a change in the approach to learning, and a change in the learning environment.

The change in thinking that I refer to requires a move away from lower-order thinking that dominates our society and results in the desire for a quick fix to all our challenges. I often refer to this quick-fix thinking in education because I spend most of my time in this discipline. For example, the educational technology (Edtech) literature for the past several decades is filled with examples of how the application of technology in a learning setting makes no significant difference and has little impact on learning outcomes and that the focus needs to be the learning, not the technology if we want to make a difference (Reich, 2020; Cuban, 2001; Russel, 1999; Wenglinsky, 1998). The research is clear. Edtech is not a quick fix or silver bullet (Thibodeaux, Harapnuik, Cummings, & Wooten, 2017) and the naive notion that one can implement it better than the last group that failed is continually repeated in all levels of classrooms across the nation (Harapnuik, 2021). This is why worksheets and fill-in-the-blank questions even when they are digitized in things like the SAMR model or other quick fixes do not result in deeper learning (Harapnuik, 2017).

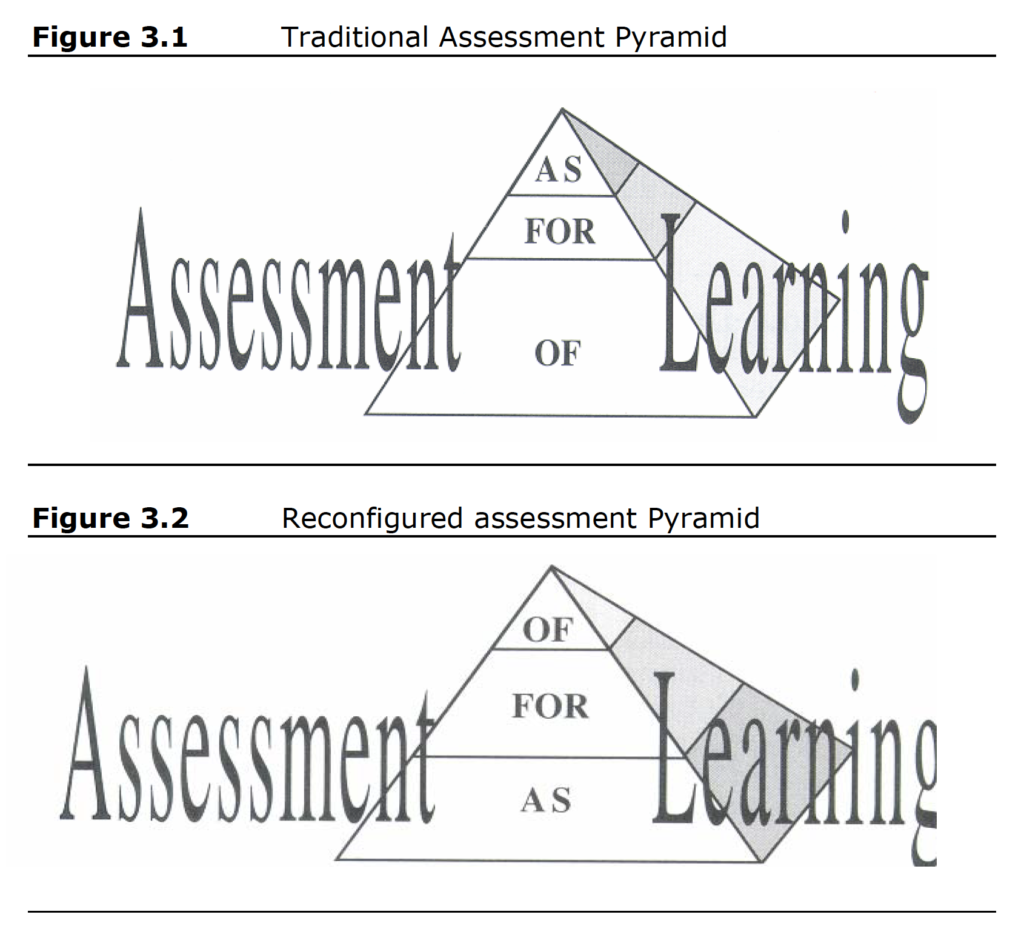

When I originally explored why this reliance on lower-order thinking continually persists I naively assumed that we could simply move up to higher thinking to high-order thinking because it incorporates the lower levels and it also has the potential to offer so much more. Unfortunately, the move to higher-order thinking involves more than just the desire to operate at that level. Besides being much easier than higher-order or deeper thinking, lower-order thinking offers a sense of security because it is what our educational system has prepared most people to do. Standardized testing and the competency-based system of education that uses this form of summative assessment exist primarily in the realm of applying, understanding, and remembering which fall into the lower-order thinking in Bloom’s Taxonomy.

While we do have pockets of outcome-based instruction where students are given choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities or project-based learning, for the most part, our system relies on information transfer and competency-based instruction which resides in the realm of lower-ordered thinking which can be easily measured. The philosopher, Steven Hicks (2021) argues that our current education system is one that teaches compliance, and rather than learning that life is about solving problems our students are instructed that authorities have all the answers. We use the rhetoric of Dewey and say we want children to grow to be self-reliant, creative problem-solving adults but we have the reality of Thorndike that promotes the information transfer standardized model of education that can be easily measured and allows us to sort our students into the fixed norms of the industrial age (Labaee, 2005). I have listed several obstacles to higher-order thinking but I think the biggest challenge is that most people don’t really understand the difference between the two levels. Furthermore, many don’t realize that learners are seldom asked to move beyond showing they can remember information, can understand how information is used, and how that information is applied in a different yet similar situation.

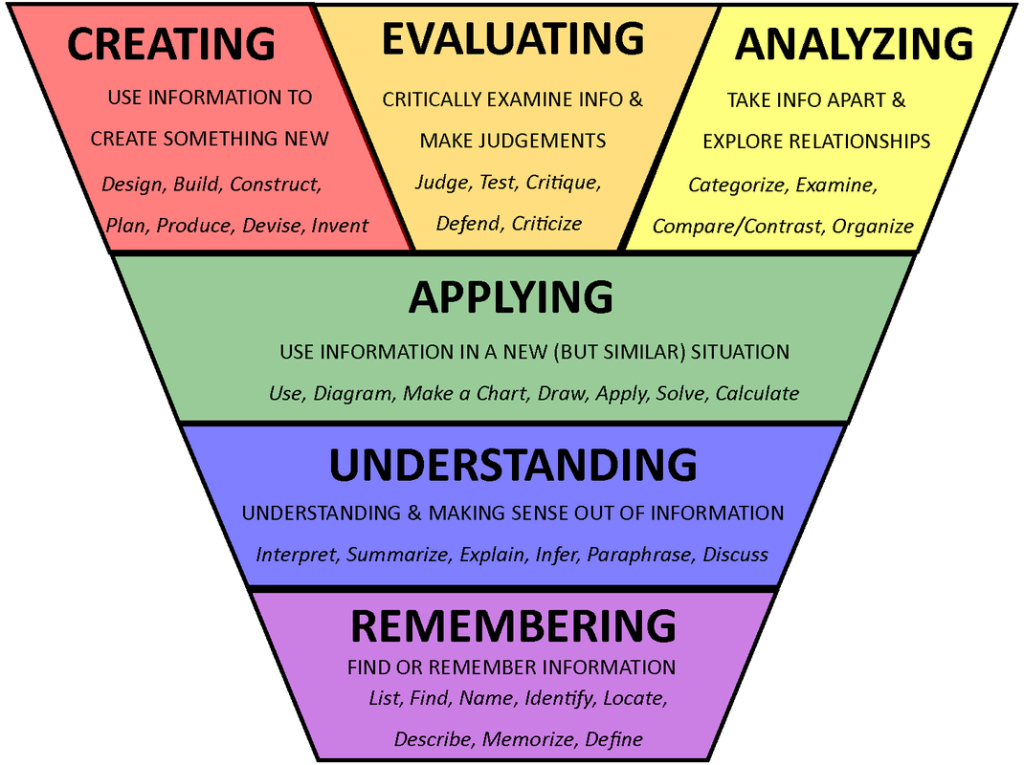

Bloom’s Taxonomy

According to the revised Bloom’s taxonomy when people are attempting to carry out a procedure or implement a process or apply an existing model to a new but similar situation they are using lower-ordering thinking in their hopes of applying existing information to their situation (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). The category of Applying is at the top of the lower-order thinking within Bloom’s taxonomy but it is still considered lower-order thinking and only facilitates information transfer because there is no analysis, evaluation, or creation which are at the higher order and are essential to deeper learning. Drawing a diagram, making a chart, applying an existing process, and solving a formula are all lower-level skills that do not require higher-order thinking and this is typically as far as our education system goes.

I prefer to use the inverted Bloom’s taxonomy because it combines higher-order thinking into a continuum and reveals that analyzing, evaluating, and creating must be conducted in conjunction. The notion of using the information in a new but similar situation detailed in the Applying section seems to match the level of thinking that many students are comfortable with. But, don’t take my word for this. In the following 3 Learner’s Stories podcast Applied Digital Learning (ADL) students reflect on their learning journey and discuss what they have learned and what they would do differently if there were able to start the ADL program now. One of the most consistent laments is that ADL students wished they would have trusted the ADL process sooner and moved away from expecting to be told what to do and simply giving the instructors what they wanted.

COVA Podcast LM Stories EP08

View on Youtube – https://youtu.be/95PpBnkBAxk

Listen on Spotify – https://open.spotify.com/episode/5M5YnqRzG98l3nSHCCc5LY?si=33d092e4d0c04f9d

COVA Reflection LM Stories Ep 09

View on Youtube – https://youtu.be/t4PTGr1WjLI

Listen on Spotify – https://open.spotify.com/episode/2uumYGwgQkUSnsZc1dTYUu?si=61fdbf1a2bde4ecf

COVA Capstone LM Stories Ep 10

View on Youtube – https://youtu.be/ctaKftOOye8

Listen on Spotify – https://open.spotify.com/episode/39c65g9KB4H1DFL5eofico?si=e9c5fba740b84f97

This desire and comfort level of being told what to do and being given a checklist prescription of what is required to complete an assignment falls directly into the lower-order thinking that most of our learners are accustomed to. The original definition from Anderson, Krathwohl, and Bloom’s (2001) of Bloom’s taxonomy aligns with what I have seen with many students:

Applying: Carrying out or using a procedure through executing or implementing. Applying is related and refers to situations where learned material is used through products like models, presentation, interviews, and simulations.

Many just want to be told what procedure or model they need to execute or implement and believe that all they have to present an existing model to their colleagues or simulate the applied approach, and their innovation process is complete. To be fair to many of these students, this is what they know and simply what their administrators, schools, districts, or other organizations ask them to do. Applying an existing model, presenting a summary, and even creating a simulation or a model is the norm. This ongoing process of identifying a standard to be met, finding the approved or accepted procedure or process being used in the organization to meet this standard, and finally applying a standardized test or other information transfer confirmation tools to confirm that the standard has been met by the students is what most educators are engaged in on a daily basis. For rudimentary knowledge, simple situations, and information transfer this application process does work well and our education system has been relying on this model for over a century. As we move further into the digital information age we are realizing that our challenges are much more complex and require much more than doing what we have done in the past. To address these more significant challenges we need to move beyond applying existing information or processes in a new but similar fashion.

Moving to Higher Order Thinking

We need to move into analyzing, evaluating, and creating new solutions to ever-increasing challenges that we and our learners will face in the future. We also need to look beyond convenient summaries, quick fixes, or “Coles Notes” solutions and go back to primary sources to get the full picture. If we want to address the ever-increasing complexities of the challenges we face in the 21st Century then we must use higher-order thinking. We must continually investigate, explore, analyze and evaluate what we are doing as we begin creating innovations that will enhance learning. Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) explanation of the following three higher thinking levels offers the best starting point for our own analysis, evaluation, and creation of a novel way of integrating these ideas.

Analyzing: Breaking material or concepts into parts, determining how the parts relate or interrelate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose. Mental actions include differentiating, organizing, and attributing as well as being able to distinguish between components.

Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing.

Creating – Putting elements together to form a novel coherent whole or make an original product.

Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating Leads to Deeper Learning and Learner’s Mindset

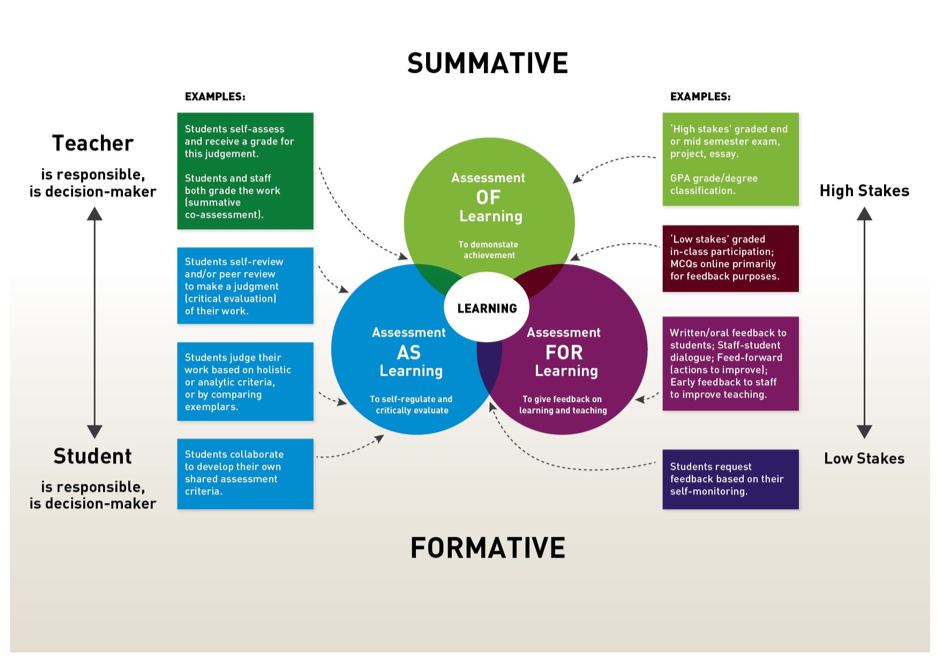

While the inverted Bloom’s taxonomy is useful for helping us to see the linear relationship between analyzing, evaluating, and creating and also see how higher-order thinking is separated from lower-order thinking, it doesn’t convey the interrelatedness between analyzing, evaluating, and creating. It also doesn’t show how the interrelation between analyzing, evaluating, and creating contributes to deeper learning.

The Venn diagram (Harapnuik, 2021) reveals how analyzing, evaluating, and creating come together and at that convergence point is where the learner engages in deeper learning and has then moved into the Learner’s Mindset.

This deeper learning and the adoption of a Learner’s Mindset is realized when you create a significant learning environment in which you give your learner choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities (CSLE+COVA). I have been applying this approach in all the learning environments that I have created and most recently have applied this to the DLL and ADL programs, the Provincial Instructor Diploma Program (PIDP), and all other aspects of my professional and personal life.

In my original post that I referenced at the beginning of this post, I made the grandiose goal of changing the world one learner at a time. A year later, I am still sharing this approach with as many people as I can. It is my hope that you too will begin the ongoing process of analysis, evaluation, and creation. Through a continual and iterative process of analysis of your learning environment, the new concepts, theories, and ideas you are exploring combined with your goal of bringing learning innovation to your organization, you too can begin to explore and evaluate how best to synthesize your findings and ideas into an innovation plan which will create the changes you desire and prepare your learners for life.

Please remember that this is only one part of a bigger picture and this synthesis will be continually evaluated and analyzed so explore the following and provide your feedback to help this ongoing process:

Applied Learning

Assessment Of/For/As Learning

Connecting the Dots Vs Collecting, the Dots

Change of Focus

CLSE

COVA

Feedforward

Learner’s Mindset

Continue to Part 2 – The challenges of owning your learning and higher-order thinking (Part 2)

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Abridge Edition). Addison.

Cuban, L. (2001). Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Harvard University Press.

Harapnuik, D.K. (2021). Analyze-evaluate-create-deeper-learning-cropped.png. [Image] https://www.harapnuik.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Analyze-Evaluate-Create-Deeper-Learning-cropped.png

Harapnuik, D.K. (2021). How to change the world, one learner, at a time. [Blog] Retrieved from https://www.harapnuik.org/?p=5555

Harapnuik, D.K. (2017). Reconsider the use of the SAMR model. [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.harapnuik.org/?p=7235

Reich, J. (2020). Failure to disrupt: Why technology alone can’t transform education. Harvard University Press.

Labaree, D. F. (2005). Progressivism, schools and schools of education: An American romance. Paedagogica Historica, 41(1–2), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/0030923042000335583

Russell, T. L. (1999). The no significant difference phenomenon: A comparative research annotated bibliography on technology for distance education: As reported in 355 research reports, summaries, and papers. North Carolina State University.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., Cummings, C. D., & Wooten, R. (2017). Learning all the time and everywhere: Moving beyond the hype of the mobile learning quick fix. In Keengwe, J. S. (Eds.). Handbook of research on mobile technology, constructivism, and meaningful learning. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Wenglinsky, H. (1998). Does it compute? The relationship between educational technology and student achievement in mathematics. ETS Policy Information Center. https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/PICTECHNOLOG.pdf