https://youtu.be/zABwof_oYrw

Archives For Innovation

If you have spent any time working in or around our educational system at almost any level then you will recognize the following responses that are all too often offered by school board members, superintendents, principals, teachers, and parents when faced with challenging problems or responding to innovative opportunities:

1. Find a scapegoat. Teachers can blame administrators, administrators can blame teachers, both can blame parents, and everyone can blame the system.

2. Profess not to have the answer. That lets you out of having any answer.

3. Say that we must not move too rapidly. That avoids the necessity of getting started.

4. For every proposal set up an opposite and conclude that the “middle ground” (no motion whatever) represents the wisest course of action.

5. Point out that an attempt to reach a conclusion is only a futile “quest for certainty.” Doubt and indecision promote growth.

6. When in a tight place, say something that the group cannot understand.

7. Look slightly embarrassed when the problem is brought up. Hint that it is in bad taste, or too elementary for mature consideration, or that any discussion of it is likely to be misinterpreted by outsiders.

8. Say that the problem cannot be separated from other problems. Therefore, no problem can be solved until all other problems have been solved.

9. Carry the problem into other fields. Show that it exists everywhere; therefore it is of no concern.

10. Point out that those who see the problem do so because of personality traits. They see the problem because they are unhappy— not vice versa.

11. Ask what is meant by the question. When it is sufficiently clarified, there will be no time left for the answer.

12. Discover that there are all sorts of dangers in any specific formulation of conclusions; of exceeding authority or seeming to; asserting more than is definitely known; of misinterpretation by outsiders— and, of course, revealing the fact that no one has a conclusion to offer.

13. Look for some philosophical basis for approaching the problem, then a basis for that, then a basis for that, and so on back into Noah’s Ark.

14. Retreat from the problem into endless discussion of various ways to study it.

15. Put off recommendations until every related problem has been definitely settled by scientific research.

16. Retreat to general objectives on which everyone can agree. From this higher ground, you will either see that the problem has solved itself, or you will forget it.

17. Find a face-saving verbal formula like “in a Pickwickian sense.”

18. Rationalize the status quo; there is much to be said for it.

19. Introduce analogies and discuss them rather than the problem.

20. Explain and clarify over and over again what you have already said.

21. As soon as any proposal is made, say that you have been doing it for 10 years. Hence there can’t be possibly any merit in it.

22. Appoint a committee to weigh the pros and cons (these must always be weighed) and to reach tentative conclusions that can subsequently be used as bases for further discussions of an exploratory nature preliminary to arriving at initial postulates on which methods of approach to the pros and cons may be predicated.

23. Wait until some expert can be consulted. He will refer the question to other experts.

24. Say, “That is not on the agenda; we’ll take it up later.” This may be repeated ad infinitum.

25. Conclude that we have all clarified our thinking on the problem, even though no one has thought of a way to solve it.

26. Point out that some of the greatest minds have struggled with this problem, implying that it does us credit to have even thought of it.

27. Be thankful for the problem. It has stimulated our thinking and has thereby contributed to our growth. It should get a medal.

Other than the phrase “in a Pickwickian sense” which refers to Mr. Pickwick in Dickens’s Pickwick Papers and refers to being especially jovial in order to avoid offense, chances are you have heard one or many of these excuses used when challenging questions are asked, problems are being pointed out, or innovative opportunities are being promoted.

Perhaps the most sobering consideration about this list is that it was compiled by the progressive educator Paul Diederich in 1942. Deidrich was part of intense discussions with hundreds of teachers during summers in the late-1930s when the Eight-Year Study was being implemented in 30 high schools across the US. The study revealed that graduates of these more progressive schools which offered artistic, political, and social activities did as well academically as graduates from more traditional schools. Unfortunately, these reforms in the schools in the study demished within the next decade and by the 1950s there was a return to the fundamentals and a focus on the mechanics of spelling instead of a focus on the writing assignment as being part of a something authentic or part of the real world. As we face the challenges of moving our educational system from the industrial age to digital information age we must remember that this is a long-term challenge and we should heed Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr epigram:

The more things change, the more they stay the same

The educational historian Larry Cuban offers additional information and links in the post Educator Discussions That Avoid “The Problem” on his site from where I copied this list.

References

Cuban, L. (2018, November 30). Educator discussions that avoid “The Problem”. [Blog] Retrieved from: https://larrycuban.wordpress.com/2018/11/

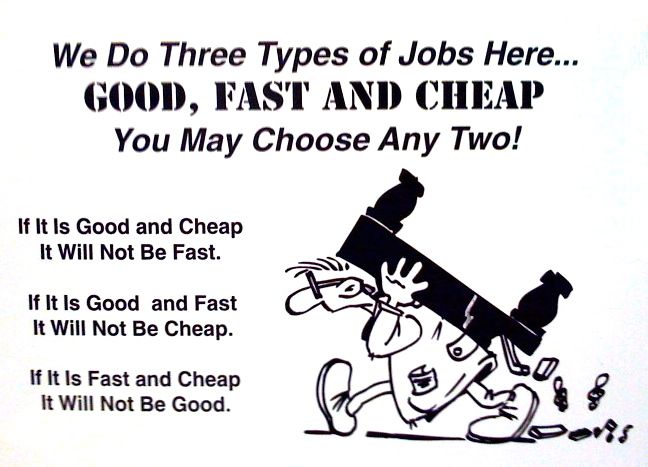

Back in 2013, I wrote a post titled Pick Two – Innovation, Change or Stability where I used the following constraint triad:

When I applied it to Education I came up with:

“Pick any two—innovation, change or stability”

I made the argument that this could explain why innovation was so slow to happen in education and I also challenged educational leadership and faculty to face the reality that if they really want innovation then they can’t have the levels of stability that are they are so accustomed. In my argument summary, I suggested that it is impossible to become an innovative or entrepreneurial organization by continually hiring traditional and conventional people. I also acknowledged the fact that innovative, entrepreneurial and out of the box thinkers push the limits, ask uncomfortable questions, offer unique solutions and make some people feel uncomfortable.

I have continually reflected upon and repeated the Good, Fast, and Cheap — Pick Two constraint triad so when I saw Seth Godin’s blog First, Fast, and Correct I immediately knew I had another useful constraint tool to add to my ideas toolbox. Godin’s post is so short and concise that I will simply repeat it:

First, fast and correct

All three would be great.

First… you invent, design, develop and bring to life things that haven’t been done before.

Fast… you get the work done quickly and efficiently.

Correct… and it’s right the first time, without preventable errors.

Being first takes guts. Being fast takes training. And being anyone takes care.

All three at once is rare. Two would be great. And just one (any one) is required if you want to be a professional.

Alas, too often, in our confusion about priorities and our fear of shipping, we end up doing none and settling for average instead.

I think that the final statement is key to understanding why constraints are so important. If you do not focus on just one priority and try to do all three you may not achieve any of the desired results or if you are lucky you have to settle for an average which is just another term mediocrity.

Constraints are extremely important because they force one to make choices. When one makes choices the consequences of those choices will be realized. If we recognize this going in we can effectively use choice and constraints o get the results we want. If we want to be first or innovative then we can make this choice and recognize that a trade-off may be accepting some level of errors or some loss of speed. But that is OK if we recognize this going in. It will also mean that we may need to get used to the fact that errors and error correction are simply part of the process of inventing, design, developing and bring to life things that haven’t been done before.

Are you using constraints to help you make effective choices? Are you trying to do it all and settling for nothing or mediocrity? The choice is yours.

References

Godin. S. (2018). First, fast, and correct. [Blog]. Retrieved from: https://seths.blog/2018/09/first-fast-and-correct/