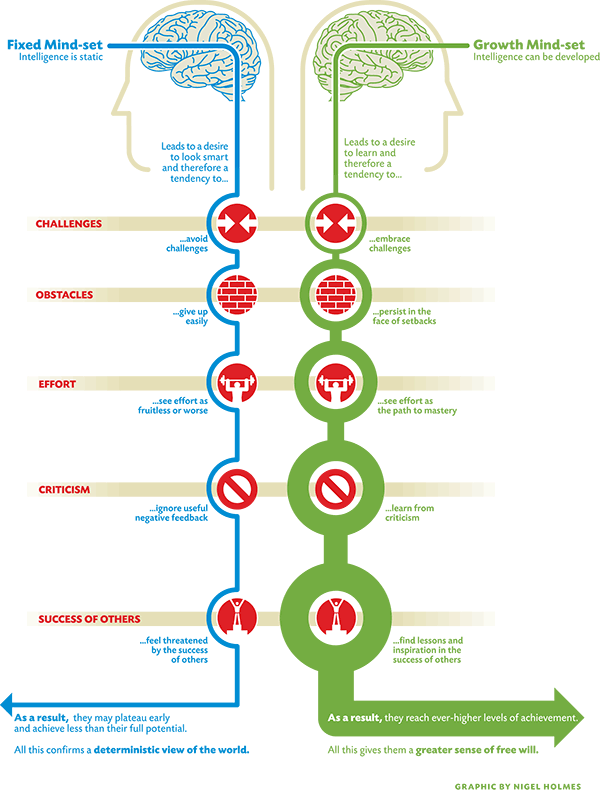

Even though constructivist learning theorists for many decades promoted the benefits of self-directed learning or autodidactism it wasn’t until the COVID crisis of 2020 and the mass forced remote learning that most educators had realized that too many students were not suited or prepared to learn online. Why? Justin Reich (2020) points to research in his book, A Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education, which shows that the learners who are most successful in an online or blended environment that requires self-pacing and personal motivation are those who are already successful in school. These self-directed, self-motivated, and academically prepared learners will succeed in any learning environment because they know how to learn and assess the quality of their own work. The problem that we face is that the vast majority of students are dependent on their teachers to direct their learning and to administer standardized testing. If autodidactic learners are able to learn in any type of environment then we should be asking how do we help our learners become autodidacts and adopt a learner’s mindset. I have explored this notion further in the post, We Need More Autodidacts and the related Learner’s Mindset Discussion.

Our research in the Digital Learning and Leading (DLL) program at Lamar University, our experience in the School of Instructor Education at Vancouver Community college over the past several years, and several decades of related research and experience in a wide variety of learning environments have confirmed that if you create a significant learning environment where you give your learners choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities (CSLE+COVA) you can incorporate assessment FOR/AS learning which can help shift a learner toward a learner’s mindset. We have also learned through our experience and research that incorporating feedforward or educative formative assessment will also help to continue that shift toward the learner’s mindset. By giving learners choice over most aspects of their learning experience and through the use of authentic learning opportunities and ePortfolios, our students over the past several years have incorporated many aspects of the assessment as learning perspective which are essential to the learner’s mindset.

Unfortunately, all too often there is a very different learning environment that our students experience in the courses and programs I have developed and instructed than the type of the learning environment that my students are able to create for their learners in their organizations. Finding the right balance between assessment of learning, assessment for learning, and assessment as learning is one more factor that plays a significant role in the learning environment. In much the same way that we have explored and differentiated the role of choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities we have to do the same for assessment OF/FOR/AS learning.

Rather than add to the decades of literature on assessment OF/FOR/AS learning I will draw upon the key ideas and summarize the salient points that are most important to contributing to a significant learning environment.

For those who prefer a more typical written definition the New South Wales (Australia) Education Standards Authority (2017) provide a good summary of “assessment for, as, and of learning”

Assessment of learning assists teachers in using evidence of student learning to assess achievement against outcomes and standards. Sometimes referred to as ‘summative assessment’, it usually occurs at defined key points during a teaching work or at the end of a unit, term or semester, and may be used to rank or grade students. The effectiveness of assessment of learning for grading or ranking purposes depends on the validity, reliability, and weighting placed on any one task. Its effectiveness as an opportunity for learning depends on the nature and quality of the feedback.

Assessment for learning involves teachers using evidence about students’ knowledge, understanding, and skills to inform their teaching. Sometimes referred to as ‘formative assessment’, it usually occurs throughout the teaching and learning process to clarify student learning and understanding.

Assessment as learning occurs when students are their own assessors. Students monitor their own learning, ask questions and use a range of strategies to decide what they know and can do, and how to use assessment for new learning.

The following assessment OF/FOR/AS learning table is a compilation of from a wide variety of resources that goes a bit further than simple definitions (Chappuis et al., 2012; Fenwick & Parsons, 2009; McNamee & Chen, 2005; Rowe, 2012; Schraw, 2001; Sparks, 1999):

| Assessment | Of Learning | For Learning | As Learning |

| Type | Summative | Formative | Formative |

| What | Teachers determine the progress or application of knowledge or skills against a standard. | Teachers and peers check progress and learning to help learners to determine how to improve. | Learner takes responsibility for their own learning and asks questions about their learning and the learning process and explores how to improve. |

| Who | Teacher | Teacher & Peers | Learner & Peers |

| How | Formal assessments used to collect evidence of student progress and may be used for achievement grading on grades. | Involves formal and informal assessment activities as part of learning and to inform the planning of future learning. | Learners use formal and informal feedback and self-assessment to help understand the next steps in learning. |

| When | Periodic report | Ongoing feedback | Continual reflection |

| Why | Ranking and reporting | Improve learning | Deeper learning and learning how to learn |

| Emphasis | Scoring, grades, and competition | Feedback, support, and collaboration | Collaboration, reflection, and self-evaluation |

If we want to encourage our learners to become more autodidactic it would then seem reasonable to shift from assessment of learning to assessment for learning and ultimately get to assessment as learning. We see this perspective from Lorna Earl (2012) in her highly cited text Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximise Student Learning.

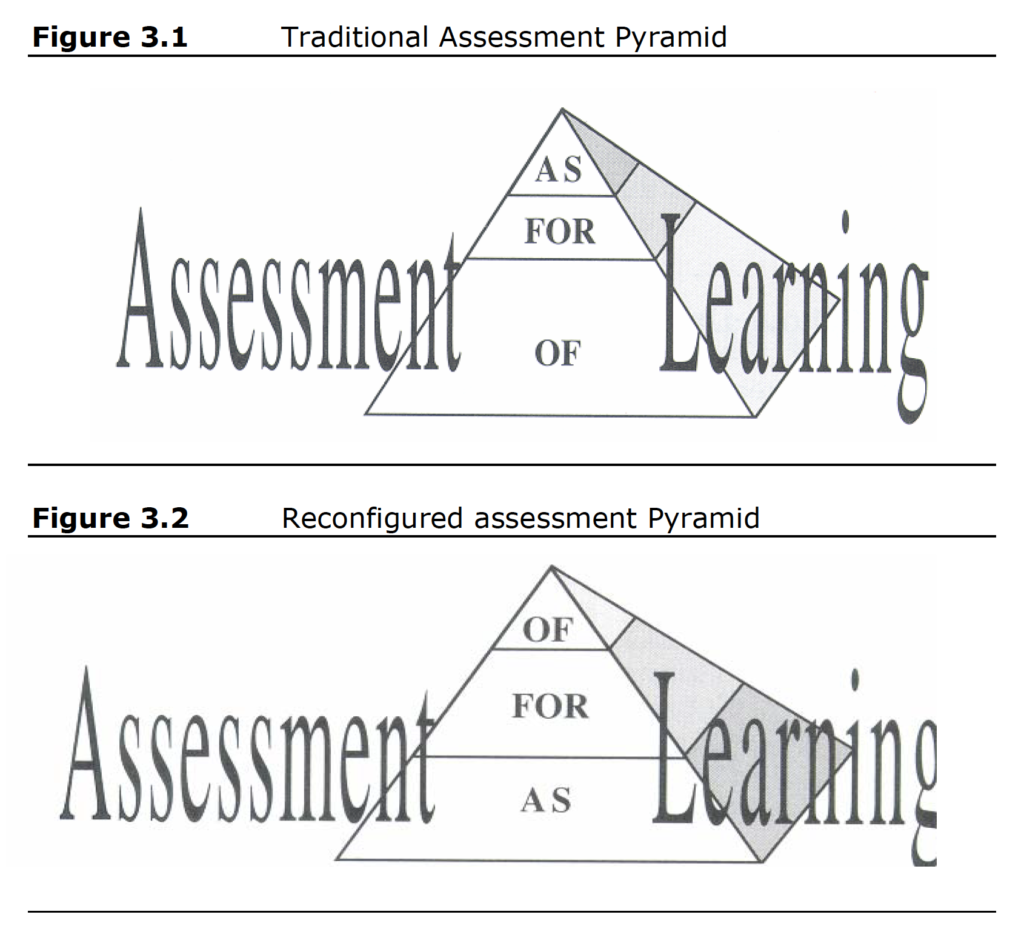

Earl’s assessment pyramids are featured in many different sources and her argument that the traditional assessment of learning is the dominant form of assessment is widely accepted. Even though she calls for a balance in the use of assessment of/for/as learning her revised assessment pyramid that replaces assessment of learning with assessment as learning as the base of the pyramid still doesn’t represent a realistic balance nor an effective way to incorporate assessment into the learning environment.

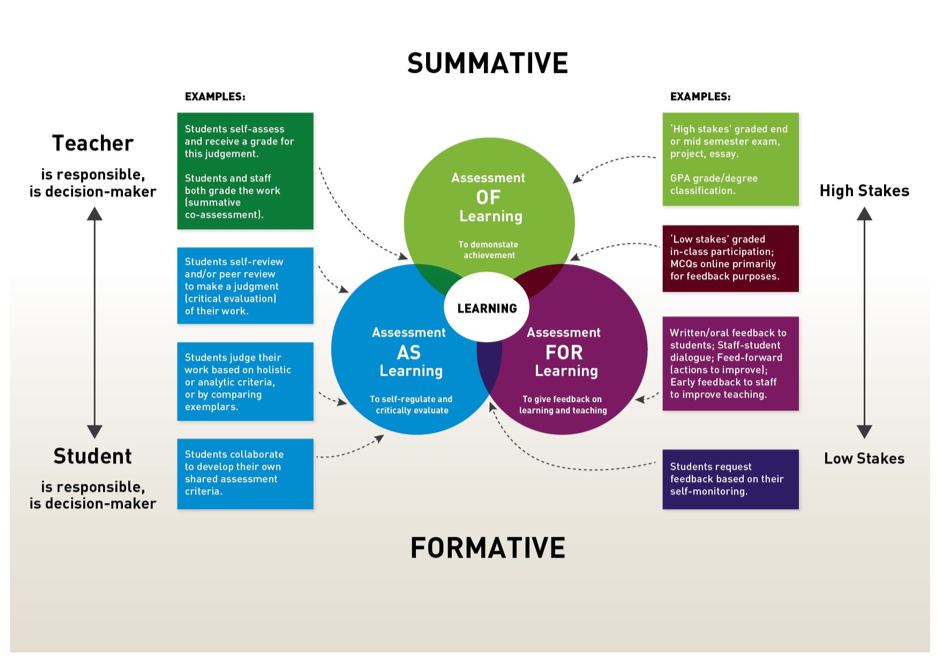

Rather than view assessment of/for/as learning as hierarchical it may be more effective to view assessment of/for/as learning more holistically as more of an interplay of assessment within the learning environment. The National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education in Ireland (2017) offers a wonderful perspective on assessment of/for/as learning that emphasizes the interplay of the different types of assessment and the key roles that the assessment and the people involved play.

While some learning theorists may desire to craft a potential learning environment that uses assessment as learning, the reality we face, and that our learners face is not theoretical. We live in a world where we use credentialing exams and other forms of standardized testing and while we have seen a recent move toward implementing formative feedback most educators’ reality reveals that assessment of learning dominates. Moving toward assessment for learning and assessment as learning will only be possible if we look at the bigger picture. We need to help educators to recognize that we are not asking for a full pendulum swing away from assessment of learning to assessment as learning with assessment for learning somewhere in the middle. We are acknowledging that an interplay of all three is not only realistic it will be the most productive approach to improving the learning environment.

We must also acknowledge that our teaching and learning environment are dramatically influenced by the assessments we use. If we consider assessment of/for/as learning as an integral part of the learning environment and we look to fully integrate assessment as part of the learning process then we do our learners justice by helping them to experience a balance in the assessment of/for/as learning. If we model an integrated approach to assessment of/for/as learning then we will be equipping our learners so that they too can integrate assessment of/for/as learning into their own learning environments that they create for their learners.

While this more focused examination of assessment of/for/as learning may provide a novel perspective for some, we have been incorporating the assessment of/for/as learning inter-relationship in the creation of our significant learning environments and when we give learners choice, ownership and voice through authentic learning. This assessment as learning perspective is a practical way to move into what the researcher Mizerow would argue is transformational learning. Mizerow (2000 & 2010) argues that you do not learn things until you tell someone about what you have learned. The transformation to deeper learning happens in the reflective process and the sharing of your learning process with others.

The entire shift toward the learner’s mindset includes the shift toward assessment as learning and you and the following posts and video are a few examples of how we have been supporting and exploring how to help learners become self-directed or autodidactic.

Related posts:

- In pursuit of the better way – the learner’s mindset

- DIY Mindset Requires a Learner’s Mindset

- Learner’s Mindset Explained

- Learners Mindset Discussions – Getting Started

- How to Grow a Growth Mindset

- Growth Mindset – How To Help Every Child Fulfil Their Potential

- Connecting dots vs collecting dots

- The Power of Deliberate Practice

References

Alberta Education. (2003). Types of classroom Assessment http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/mewa/html/assessment/types.html

Assessment OF/FOR/AS Learning. (2017, March). [National Forum]. The National Forum for the enhancement of teaching and learning in higher education. https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/our-priorities/student-success/assessment-of-for-as-learning/

Chappuis, J., Stiggins, R. J., Chappuis, S., & Arter, J. (2012). Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right-using it well. Pearson Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Earl, L. M. (2012). Assessment as learning: Using classroom assessment to maximize student learning. Corwin Press.

Earl, L. M., & Manitoba School Programs Division. (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind: Assessment for learning, assessment as learning, assessment of learning. Manitoba

Education, Citizenship and Youth. https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/assess/wncp/index.html

Fenwick, T. J., & Parsons, J. (2009). The art of evaluation: A resource for educators and trainers. Thompson Educational Publishing.

McNamee, G. D., & Chen, J.-Q. (2005). Dissolving the Line between assessment and teaching. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 72–76.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass Publishers. San Francisco, CA.

National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. (2017, March 30). Expanding our Understanding of Assessment and Feedback in Irish Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/expanding-our-understanding-of-assessment-and-feedback-in-irish-higher-education/.

NSW Education Standards Authority. (n.d.). Assessment For, As and of Learning. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/understanding-the-curriculum/assessment/approaches

Rowe, J. (2012). Assessment as learning—ETEC 510. http://etec.ctlt.ubc.ca/510wiki/Assessment_as_Learning

Schraw, G. (2001). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. In Metacognition in learning and instruction (pp. 3–16). Springer.

Sparks, D. (1999). Assessment without victims: An interview with Rick Stiggins. Journal of Staff Development, 20, 54–56.

Revised Feb 21, 2021