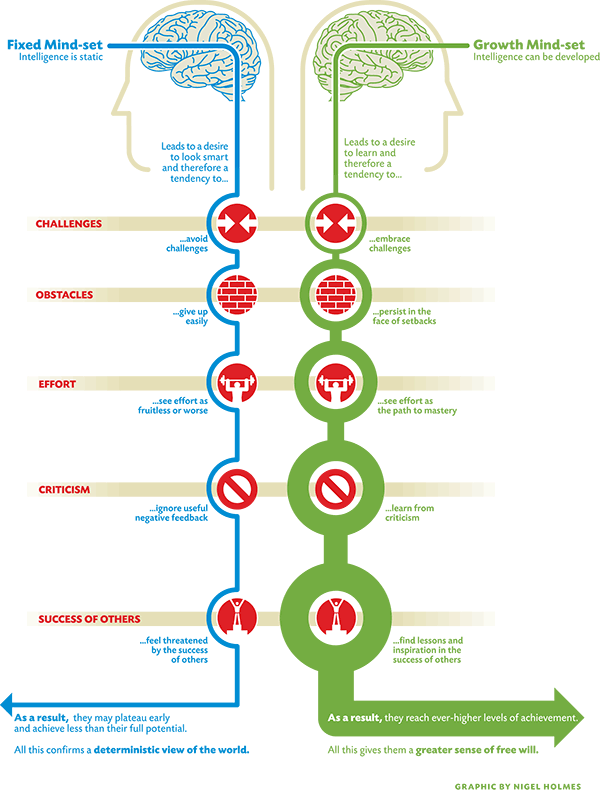

Carol Dweck, Professor of Psychology at Stanford University, the author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (Random House, 2007) posits that if students with a Fixed Mindset believe that intelligence is an inborn trait and is essentially fixed they:

- Tend to view looking smart above all else;

- May sacrifice important opportunities to learn—even those that are important to their future academic success—if those opportunities require them to risk performing poorly or admitting deficiencies;

- Believe that if you have ability, everything should come naturally;

- Tell us that when they have to work hard, they feel dumb;

- Believe that setbacks call their intelligence into question, they become discouraged or defensive when they don’t succeed right away;

- May quickly withdraw their effort, blame others, lie about their scores, or consider cheating.

In contrast Dweck explains that students with a Growth Mindset believe that they can develop their intelligence over time and subsequently will:

- View challenging work as an opportunity to learn and grow;

- Meet difficult problems, ones they could not solve yet, with great relish;

- Say things like “I love a challenge,” “Mistakes are our friends,” and “I was hoping this would be informative!”

- Value effort; they realize that even geniuses have to work hard to develop their abilities and make their contributions;

- More likely to respond to initial obstacles by remaining involved, trying new strategies, and using all the resources at their disposal for learning.

To help motivate students to adopt the growth mindset Dweck recommends that teachers create a culture of risk taking and strive to design challenging and meaningful tasks. This will require teachers to learn to encourage and reward effort, persistence and improvement rather than simply reward results and test scores. It will also mean that instructors will need to educate student on the different mindsets. Dweck offers many key recommendations that include:

There are three things that any of us can do to install a growth mindset in ourselves and those around us.

- Recognized that the growth mindset is not only beneficial but it’s also supported by science. Neuroscience shows that the brain is mailable. Our brain changes and becomes more capable when we work hard to improve ourselves.

- Learn and teach others about how to develop our abilities. We need to learn about deliberate practice and what makes for effective effort. When we learn how to develop our abilities we strengthen our conviction that we’re in charge of them.

- Listen for your fixed mind set voice and when you hear it, talk back with a growth mindset voice. If you hear “I can’t do it” at “yet”.

Dweck recommends that we make the following changes to the learning environments we create and support:

- Emphasizing Challenge, Not “Success”

- Giving a Sense of Purpose;

- Grading for Growth;

- The Power of Yet.

In the TED talk The power of believing that you can improve Dweck summarizes the advantages of adopting a growth mindset and points to ongoing research and evidence of how powerful a growth mindset can be in improving a learning environment.

The move toward adopting a growth mindset parallels our need to constantly adapt to changes in our learning environment. The post Fixed Vs Growth Mindset = Print Vs Digital Information Age outlines just how important a growth mindset is as we move from the static print information age to the dynamic digital information age.

Carol Dweck’s work is being vetted and adapted by many other researchers and educators. Eduardo Briceño is the Co-Founder and CEO of Mindset Works (http://www.mindsetworks.com), an organization that helps schools and other organizations cultivate a growth mindset culture. In his TED talks he provides another voice to the the advantages of the growth Mindset.

Growth vs Fixed Mindset

Angela Lee Duckworth research into “grit” rather than IQ as an accurate predictor of student success also uses the growth mindset as a guiding theory. Students with the most grit are those who have adopted the growth mindset. Duckworth points to Dweck’s work as the primary source of research in this area.

The key to success? Grit

In the RSA ANIMATE: How To Help Every Child Fulfil Their Potential the RSA folks provide a wonderful visual perspective on the growth mindset.