CSLE+COVA Research

Peer Reviewed eBooks

Harapnuik, D. K., & Thibodeaux, T. N. (2023). COVA: Inspire Learning Through Choice, Ownership, Voice, and Authentic Experiences 2nd Ed. Learner’s Mindset Publishing.

COVA eBook is available in Kindle format from Amazon,

Harapnuik, D. K., & Thibodeaux, T. N. (2023). Learner’s Mindset: A Catalyst for Innovation. Learner’s Mindset Publishing. KIndle format from Amazon

Published peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters that point to research that supports the COVA+CSLE approach:

Thibodeaux, T. N., & Harapnuik, D. K. (2021). Exploring students’ use of feedback to take ownership and deepen learning. International Journal of e-Learning. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/j/IJEL/

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., Cummings, C. D., & Dolce, J. (2021). Graduate students’ perceptions of factors that contribute to ePortfolio Persistence beyond the program of study. International Journal of ePortfolio.

Harapnuik, D. K., & Thibodeaux, T. N. (2020). Exploring students’ use of feedback to take ownership and deepen learning. International Journal of e-Learning. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/j/IJEL/

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., & Cummings, C. D. (2019). ePortfolio Persistence. Manuscript in progress.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., & Cummings, C. D. (2019). Feedback to Feedforward. Manuscript in progress.

Thibodeaux, T. N., & Harapnuik, D. K. (2019). Exploring students’ use of feedback to take ownership and deepen learning. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K, & Cummings, C. D. (2019). Student perceptions of the influence of the COVA learning approach on authentic projects and the learning environment. International Journal of e-Learning, 18(1), 79-101. Retrieved from http://www.learntechlib.org/c/IJEL/

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., & Cummings, C. D. (2019). Student perceptions of the influence of choice, ownership, and voice in learning and the learning environment. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 33(1), 50-62. Retrieved from

http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/current.cfm

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K, & Cummings, C. D. (2018). Graduate student perceptions of the impact of the COVA learning approach on authentic projects and ePortfolios. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., & Cummings, C. D. (2018). Perceptions of the influence of learner choice, ownership in learning, and voice in learning and the learning environment. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K, & Cummings, C. D. (2017). Graduate student perceptions of the impact of the COVA learning approach on authentic projects and ePortfolios. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., & Cummings, C. D. (2017, May). Learners as critical thinkers for the workplace of the future: Introducing the COVA learning approach. Texas Computer Education Association TCEA Techedge, 2(2), 13. Retrieved from http://www.tcea.org/about/publications/

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K., Cummings, C. D., & Wooten, R. (2017). Learning all the time and everywhere: Moving beyond the hype of the mobile learning quick fix. In Keengwe, J. S. (Eds.). Handbook of research on mobile technology, constructivism, and meaningful learning. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Harapnuik, D. K., Thibodeaux, T. N., & Cummings, C. D. (2017, March). Student perceptions of the impact of the COVA approach on the ePortfolios and authentic projects in the digital learning and leading program. Paper presented at the Society for Information Technology in Teacher Education (SITE), Austin, TX.

Harapnuik, D. K., Thibodeaux, T. N., & Cummings, C. D. (2017). Using the COVA learning approach to create active and significant learning environments. In Keengwe, J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of research on digital content, mobile learning, and technology integration models in teacher education. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Thibodeaux, T. N., Harapnuik, D. K, & Cummings, C. D. (2017). Factors that contribute to ePortfolio persistence. International Journal of ePortfolio, 7(1), p. 1-12. Retrieved from http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP257.pdf

Harapnuik, D., Thibodeaux, T. & Poda, I. (2017) New Technologies. In Martin, G.E., Danzig, A.B., Wright, W.F., Flanary, R.A., & Orr, M.T. School leader internship: Developing, monitoring, and evaluating your leadership experience (4th Ed.). New York: Routledge, pp. 91-94.

The research that informs the CSLE+COVA

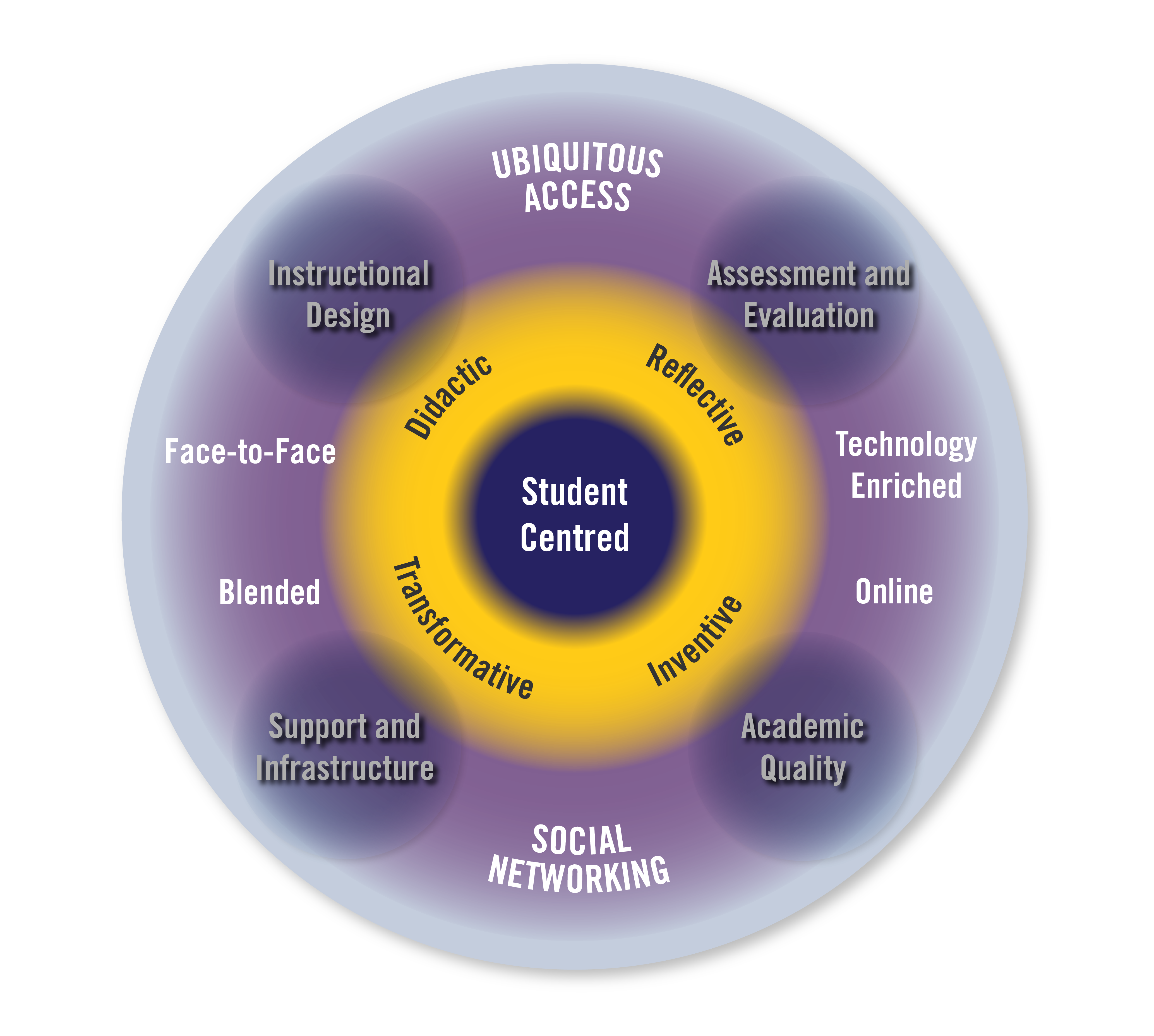

The CSLE+COVA approach is based on a considerable amount of research that has been conducted over the past two decades about what works and does not work when it comes to creating significant learning environments where learners are given choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities. While based on all the research listed in the references, in particular, it emphasizes…

Constructivism – With roots stemming from progressive education, the combination of Labaree (2005) and Hattie’s (2008) definition of constructivism builds upon student-centered learning, guided discovery learning, and visible learning where students construct new knowledge and show others how they learn (Piaget, 1964; Ginsberg & Oppers, 1969, Papert, 1993, 1997). Jonassen and Reeves (1996) assert that learning with technology or using technology tools to support the learning process, should be the focus in the learning environment rather than learning from technology. This line of thinking allows authentic projects to become the “object of activity” as opposed to technology functioning as the primary focus of instruction.

Student/learner-centered – It all has to start with the learner. Mayer (2009) characterized learner-centered approaches where instructional technology was used as an enhancement to human cognition. Essentially, student-centered learning is when students “own” their own learning (Dewey, 1916; Lee & Hannafin, 2016).

Teaching roles – An instructor has many different roles which at minimum include presenter, facilitator, coach, and mentor (Harapnuik, 2015a; Priest, 2016). We need to shift to more coaching and mentoring because formative evaluation and feedback given within a trusted relationship yields the highest levels of student achievement (Hattie 2008, 2011).

Ubiquitous Access & Social Networking – We live in an age where we can access all the world’s information and almost anyone from the palms of our hands. Because we are socially networked and connected learners look to their peers and crowd-sourcing for information and solutions to problems (Edelman, 2017).

Instructional Design — If we start with the end in mind or a purposeful backward design, we can look at how a course or program will change learners’ lives, how it can make them a better member of society, and how they can contribute to solving particular problems (Fink, 2003; Harapnuik, 2004, 2015a).

Assessment & Evaluation — We should be incorporating formative tools like feed forward (Goldsmith, 2009) or educative assessments that help the learner to align outcomes with activities and assessment (Fink, 2003).

Support & Infrastructure — When people talk about learning technology, they think of tablets and laptops being used in the classroom or learning management systems. But this is the wrong focus; we should not focus on the technology itself but viewed simply as a tool that provides information and supports teaching and learning (November, 2013; Amory, 2014).

Choice – Learners are given the freedom to choose how they wish to organize, structure, and present their learning experiences (Dewey, 1916, Ginsberg & Opper, 1969). Choice also extends to the authentic project or learning experience promotes personalized learning (Bolliger & Sheperd, 2010) which includes adapting or developing learning goals and choosing learning tools that support the learning process (Buchem, Tur, & Hölterhof, 2014).

Guided discovery – It is crucial to acknowledge that the learner’s choice is guided by the context of the learning opportunity and by the instructor who aides the learner in making effective choices. The research over the past 40 years confirms guided discovery provides the appropriate freedom to engage in authentic learning opportunities while at the same time providing the necessary guidance, modeling, and direction to lessen the cognitive overload (Bruner, 1961, 1960; Ginsberg & Opper, 1969: Mayer, 2004).

Ownership – Constructivists, like Jonassen (1999), argue that ownership of the problem is key to learning because it increases learner engagement and motivation to seek out solutions. Ownership of learning is also directly tied to agency when learners make choices and “impose those choices on the world” (Buchem et al., 2014, p. 20; Buchem, Attwell, & Torres, 2011). Clark (2001) points to a learner’s own personal agency and ownership of belief systems as one major factor contributing to the willingness and persistence in sharing their learning.

Voice – Learners are given the opportunity to use their own voice to structure their work and ideas and share those insights and knowledge with their colleagues within their organizations. The opportunity to share this new knowledge publicly with people other than the instructors helps the learner to deepen their understanding, demonstrate flexibility of knowledge, find their unique voice, establish a sense of purpose, and develop a greater sense of personal significance (Bass, 2014).

Authentic learning – The selection and engagement in real-world problems that are relevant to the learner further their ability to make meaningful connections (Donovan et al., 2000) and provide them with career preparedness not available in more traditional didactic forms of education (Windham, 2007). Research confirms that authenticity is only developed through engagement with these sorts of real-world tasks or as Kolb (1974 & 2014) would suggest through experiential learning and that this type of authentic learning can deepen knowledge creation and ultimately help the learner transfer this knowledge beyond the classroom (Driscoll, 2005; Nikitina, 2011). It is also important to recognize that authenticity is not an independent or isolated feature of the learning environment but it is the result of the continual interaction between the learner, the real-world activity, and the learning environment (Barab, Squire, & Dueber, 2000). This is also why we stress that in the COVA model choice, ownership, and voice are realized through authentic learning, and without this dynamic and interactive authenticity, there would be no genuine choice, ownership, and voice (Harapnuik, Thibodeaux, & Cummings, 2017).

References

Amory, A. (2014). Tool-mediated authentic learning in an educational technology course: A designed-based innovation. Interactive Learning Environments, 22(4), 497-513. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2012.682584

Barab, S. A., Squire, K. D., & Dueber, W. (2000). A co-evolutionary model for supporting the emergence of authenticity. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(2), 37–62.

Bass, R. (2014). Social pedagogies in ePortfolio practices: Principles for design and impact. Retrieved from http://c2l.mcnrc.org/pedagogy/ped-analysis/

Bolliger, D. U., & Sheperd, C. E. (2010). Student perceptions of ePortfolio integration in Online courses. Distance Education, 31(3), 295-314.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32.

Bruner, J. S. (1962). On knowing: essays for the left hand. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Bruner, J. S. (1973). Beyond the information given. New York, New York: Norton.

Buchem, I., Attwell, G., & Torres, R. (2011). Understanding personal learning environments: Literature review and synthesis through the activity theory lens. Proceedings of the PLE Conference, 1-33. Retrieved from http://journal.webscience.org/658/

Buchem, I., Tur, G., & Hölterhof, T. (2014). Learner control in personal learning environments: cross-cultural study. Journal of Literacy and Technology, 15(2), 14-53. Retrieved from http://www.literacyandtechnology.org/volume-15-number-2-june-2014.html

Clark, R. (2001). Learning from media: Arguments, analysis, and evidence. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. New York, New York: D. C. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to philosophy of education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Driscoll, M. P. (2005) Psychology of Learning for Instruction. Toronto, ON: Pearson.

Edelman, R. (2017). 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer. Retrieved from http://www.edelman.com/trust2017/

Fink, D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco: CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ginsburg, H., & Opper, S. (1969). Piaget’s theology of intellectual development: An introduction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Goldsmith, M. (2009). Take it to the next level: What got you here, won’t get you there. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Harapnuik, D. (2004). Development and evaluation of inquisitivism as a foundational approach for web-based instruction (Doctoral dissertation). University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Harapnuik, D. (2015, May 8b). Creating significant learning environments (CSLE). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/eZ-c7rz7eT4

Harapnuik, D. K., Thibodeaux, T. N., & Cummings, C. D. (2017). Using the COVA learning approach to create active and significant learning environments. In Keengwe, J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of research on digital content, mobile learning, and technology integration models in teacher education. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2011, November 28). Visible learning Pt1. Disasters and below average methods [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/sng4p3Vsu7Y

Jonassen, D. H. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. M. Reigeluth, Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (pp. 215-240). New York, NY: Routledge.

Jonassen, D. H., & Reeves, T. C. (1996). Learning with technology: Using computers as cognitive tools. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on education communications and technology (pp. 6930719). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Labaree, D. F. (2005). Progressivism, schools, and schools of education: An American romance. Paedagogica Historica, 41(1&2), 275-288. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ748632

Jonassen, D. H. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. M. Reigeluth, Instructional-design theories, and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kolb, David A. 2014. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

Kolb, David Allen, and Ronald Eugene Fry. 1974. Toward an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning. MIT Alfred P. Sloan School of Management.

Lee, E. & Hannafin, M. J. (2016). A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: Own it, learn it, and share it. Educational Technology Research Development, 64, 707-734. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9422-5

Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning? American Psychologist, 59(1), 14–19. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.lamar.edu/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.14

Nikitina, L. (2011). Creating an authentic learning environment in the foreign language classroom. International Journal of Instruction, (4)1, 33-36. Retrieved from http://www.e-iji.net/dosyalar/iji_2011_1_3.pdf

November, A. (2013, February 13). Why schools must move beyond one-to-one computing [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://novemberlearning.com/educational-resources-for-educators/teaching-and-learning-articles/why-schools-must-move-beyond-one-to-one-computing/

Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Papert, S. (1997). Why school reform is impossible (with commentary on O’Shea’s and Koschmann’s reviews of “The children’s machine”). The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(4), 417–427.

Piaget, J. (1964). Development and learning. In R.E. Ripple & V.N. Rockcastle (Eds.), Piaget Rediscovered: A Report on the Conference of Cognitive Studies and Curriculum Development (pp. 7–20). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Priest, S. (2016). Learning & teaching [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://simonpriest.altervista.org/LT.html#ES

Simonson, S., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2012). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Windham, C. (2007). Why today’s students value authentic learning. Educause Learning ELI Paper 9. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELI3017.pdf

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316(5827), 1036–1039.

Links to all the components of the CSLE+COVA framework:

Change in Focus

Why CSLE+COVA

CSLE

COVA

CSLE+COVA vs Traditional

Digital Learning & Leading

Research

Revised August, 2024