Archives For active learning

In the video 4 Keys to CSLE+COVA and in the upcoming CSLE+COVA book my colleagues and I are just about to release we argue that we need to take a positive approach to exploring how we improve or enhance the learning environment and we propose the following four keys or presuppositions to creating significant learning environments by giving learners choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning:

- Anything we do for the learner will improve achievement.

- There has never been a better time to be a learner.

- There really are no new fundamental approaches to learning; just new ways of combining well-established ideas.

- There is no quick fix to learning, the classroom or education.

I want to focus on the 3rd point where I argue that there really are no new fundamental approaches to learning; just new ways of combining well-established ideas. I am not alone in the assertion; Piaget made a similar claim over fifty years ago. Ginsburg and Opper (1969) point out in the summary of their book Piaget’s theology of intellectual development: An introduction:

It should be clear that these ideas are not particularly new. The “Progressive” education movement has proposed similar principles for many years. Piaget’s contribution is not in developing new educational ideas, but in providing a vast body of data and theory which provide a sound basis for a “progressive” approach to the schools. A long time ago, John Dewey, in rejecting traditional approaches to education called for and attempted to provide a “philosophy of experience”; that is a thorough explication of the ways in which children make use of experience in genuine learning. Piaget has gone a long way toward meeting this need (p. 231)

Piaget spent most of his career, over fifty years, observing and interviewing children of all ages as he gathered the data to support his theories. It is extremely important that we recognize that “none of the investigators whose theories have been used to explain the development of children—Freud, Lewin, Hull, Miller and Dollard, Skinner, Werner—has studied children as extensively as Piaget (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. x).

We should be shocked and concerned to learn that Skinner who is one of the originators of the Behaviourist approach that still dominates our educational system “hardly studied children at all” (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. x).

Despite writing over 30 full-length books and over 100 articles, being the first theorist to provide an effective empirical argument against behaviorism, and being viewed as one of the founding fathers of constructivism, Piaget full body of work is all too often ignored. Piaget’s writing may be viewed as difficult to read for a contemporary audience that may lack the necessary philosophical background. Even though many hold Piaget to be one of the foremost authorities on child development he did not intend to focus on the field of child developmental psychology but was more interested in dealing with the problems in the philosophical study of epistemology which is concerned with how we come to know and how we attain knowledge—how we learn. Piaget’s writing may be difficult to access because he is first a philosopher and only used the science of psychology to help him deal with the philosophical issues of knowledge. He also felt that many epistemological problems were essentially psychological and scientific method would help him to move from the speculation of philosophy and move more of an objective explanation.

This notion of how we come to know or make meaningful connection and essentially learn is a fundamental aspect of the CLSE+COVA approach and as we have stated earlier we owe much of our foundational thinking to Dewey, Piaget, Brunner, Papert and more contemporary authors who provide current interpretations on these foundational works. Ginsburg and Opper (1969) chapter Genetic epistemology and the implications of Piaget’s finding for education offers some the most accessible and concise summaries of Piaget’s ideas that we have incorporated into CSLE+COVA. The chapter deals with much more than what I will share below but my intention is to make Piaget’s work accessible rather than expand on his blending of philosophy and psychology. Since this particular issue of Ginsburg and Opper (1969) book Piaget’s theology of intellectual development: An introduction is out of print and only used copies are available I will share as much of the final chapter of the book that I can. Newer editions of the book are also out of print but used copies are available online. Where ever expedient I will paraphrase the writing and where it is more appropriate I will use direct quotes.

Active learning – Authentic Learning Opportunities

Perhaps the most important single proposition that an educator can derive from Piaget’s work and thus use in the classroom, is that children, especially young ones, learn best from concrete activities. (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 220).

The concrete activities that Piaget refer to can easily be mapped to the authentic learning opportunities that we recommend in COVA. Our use of the notion of authentic correlates to concrete in the sense that the activities have a “real-world” component and are activities that the learner can fully engage. Ginsburg and Opper (1969) expand on how a teacher would create this type of a Piagetian classroom or learning environment.

For these reasons a good school encourage the child’s activity and their manipulation and exploration of objects. When the teacher tries to bypass this process by imparting knowledge in a verbal manner, the result is superficial learning. But by promoting activity in the classroom the teacher exploits the child’s potential for learning and permits them to evolve an understanding of the world around them. This principle (that occurs through the child’s activity) suggests that the teacher’s major task is to provide for the child a wide variety of potentially interesting materials on which them may act. The teacher should not teach, but should encourage the child to learn by manipulating things (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 221).

This notion of active learning means that an educator must reorient traditional their beliefs about education and focus the fact that:

Teachers can, in fact, impart or teach very little. It is true that they can get the child to say certain things, but these verbalizations often indicate little in the way of real understanding. Second, it is seldom legitimate to conceive of knowledge as a thing which can be transmitted. Certainly, the child needs to learn some facts, and these may be considered things; the child must discover them for themselves. Also, facts are but a small portion of real knowledge. True understanding involves action, on both the motoric and intellectual level…The teacher’s job then is not so much to transmit facts or concepts to the child but to get them to act on both the physical and mental levels. These actions—far more than imposed facts or concepts— constitute real knowledge. (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 222).

Since information transfer isn’t the role of the teacher creating a significant learning environment in which the learner is able to discover things for themselves is the key. We would argue that this guided discover happens by giving the learner choice, ownership and voice through authentic learning opportunities.

Ownership of Learning

Equilibration theory emphasizes that the self-regulatory process are the basis for genuine learning. The child is more apt to modify their cognitive structure in a constructive way when they control their own learning than when methods of social transmission (in this case teaching) are employed. Do recall Smedslund’s experiments on the acquisition of conservation. If one tries to teach this concept to a child who does not yet have available the mental structure necessary for its assimilation, then the resulting learning is superficial. On the other hand, when children are allowed to progress at their pace through the normal sequence of development, they regulate their own learning so as to construct the cognitive structures necessary for the genuine understanding of conservation (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 224).

Ginsburg and Opper (1969) indicate that Piaget would then argue that to take these principles seriously then one must extensive change classroom practice. Teachers should:

- Be aware and assess the learners current level of understanding/functioning.

- Orient the classroom toward the individual rather than the group.

- Give the learner considerable control over their learning.

The following section summary captures what this type of learning would look like. Piaget argues that the classroom unit should be disbanded and that learners work on individual projects that they are interested in and given considerable freedom in their learning. To deal with the most common objectives to this learning arrangement Piaget suggests learners shouldn’t all be learning the same thing at the same time and that we should have more faith in the intellectual life of the learner. He stresses the importance of tailoring the learning to the individual and points out how important it is to allow the child and the adolescent to follow their interests and control how they acquire knowledge through their own directed activities apart from instruction in school and formal instruction.

Perhaps the most poignant example of how foolish it is for us to attempt to rigidly control all aspects of learning with traditional teaching methods is to consider how an infant is interested in the world around them is able to learn so much without formal instruction.

One need only watch an infant for a short period of time to know that they are curious, interested in the world around them, and eager to learn. It is quite evident, too, that these are characteristics of older children as well. If left to themselves the normal child does not remain immobile; they are eager to learn. Consequently, it is quite safe to permit the child to structure their own learning. The danger arises precisely when the schools attempt to perform the stalk for them. To understand this point consider, the absurd situations that would result if traditional schools were entrusted with teaching the infant what they spontaneously learn during the first few years. The schools would develop organized curricula, in secondary curricular reactions; they would develop lesson plans for object permanence; they would construct audio-visual aids on causality; they would reinforce “correct” speech; and they would set “goals” for the child to reach each week. One can speculate as to the outcome of such a program for early training. What the student needs then is not formal teaching, but an opportunity to learn. They need to be given a rich environment, containing many things potentially of interest. They need a teacher who is sensitive to their needs, who can judge what materials will challenge them at a given point in time, who can help when they need help and who has faith in their capacity to learn (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 224-225).

Social interaction

Piaget suggests that in addition to physical experience and concrete manipulations the learner needs social experience and interactions with a wide assortment of people. He points out that younger children learn to relinquish their egocentrism through social interaction and adjust to others at the emotional level. In addition, the social interaction helps the learner to become more coherent and logical and use language to discover reality and internalize the experience into a compact category of experience. Piaget argues:

…social interaction should play a significant role in the classroom. Children should talk with one another. They should converse, share experience, and argue. It is hard to see why schools force the child to be quiet when the results seem to be only an authoritarian situation and extreme boredom. Let us restrict the vow of silence to selected orders of monks and nuns (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 228).

Traditional Methods of Instruction

Piaget’s theory implies that there are grave deficiencies in “traditional” methods of instruction, especially in the early years of school. By “traditional” methods we mean cases in which the teacher uses a lesson plan to direct the students through a given sequence of material; attempts to transmit the material to the students by means of lectures and other verbal explanations; forces all students to cover essentially the same lessons; and employs a textbook as the basic medium for instruction. Under such an arrangement students take fixed positions in a classroom; talk to one another only at the risk of punishment; are required to listen to the teacher; must study the material which the teacher feels is necessary to study; and must try to learn from books. It is, of course, the case that teachers differ in degree to which they employ traditional methods. No two classrooms are identical, and it would be difficult to find one which is traditional in all respects and at all times. Nevertheless, traditional methods are still highly influential in education today, as even casual observations of the school reveal (Ginsburg & Opper, 1969 p. 229).

This traditional environment is based on four assumptions that have some aspect of merit but are acted upon in the traditional school in an excessive manner.

- Students at a given age level should learn the same material. While it is true that there are levels of development and age-appropriate instruction the traditional school forces students to cover the same material each day the traditional method ignores the fact that there are individual differences in the pace of learning.

- Students learn through verbal explanation from the teacher or through written exposition in books. While this has some element of truth Piaget’s research shows that students verbal explanations are only useful after a basis of concrete activity.

- If given greater control over their learning students would waste their time and learn little. If students aren’t given guidance then they would waste their time but this doesn’t mean they should have no control. Piaget points to research that a major part of learning depends on the self-regulatory process. In addition, we can’t ignore just how much students learn outside of school.

- Uncontrolled taking in class is disruptive to the educational process. Piaget points out that while excessive noise may prevent learning he also points to the fact that teachers are more distracted by noise then students. The noise is worthwhile because the clash of opinions and the intelligent and spontaneous conversations is beneficial for mental growth.

The following quote from Piaget offers a helpful summary of his educational goals:

The principle goal of education is to create [people] who are capable of doing new things, not simply of repeating what other generations have done—[people] who are creative, inventive and discoverers. The second goal of education is to form minds which can be critical, can verify, and not accept everything they are offered. The great danger today is of slogans, collective opinions, ready-made trends of thought. We have to be able to resist individually, to criticize, to distinguish between what is proven and what is not. So we need pupils where active, who learn early to find out by themselves, partly by their own spontaneous activity and partly through material we set up for them; who learn early to tell what is verifiable and what is simply the first idea to come to them (Duckworth, 1964 p. 175).

References

Ginsburg, H., & Opper, S. (1969). Piaget’s theology of intellectual development: An introduction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Duckworth, E. (1964). Piaget rediscovered. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2(3), 172–175.

The statement “we learn by doing” could be considered common sense. Perhaps it is stating the obvious and yet too many in the academic community need still need to be convinced of this fact. Freeman et al. revealed in their meta-analysis of 225 studies that compared science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) classes that:

average examination scores improved by about 6% in active learning sessions, and that students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than were students in classes with active learning.” (p. 8410)

While the 6% increase in test scores may not seem overly significant, it can make the difference between a pass or a fail. Furthermore, the data does reveal that active learning does reduce the chances of failure.

Carl Wieman, a Nobel-winning physicist who now does research on teaching and learning, argues that this extensive quantitative analysis by Freeman et al. on active learning in college and university STEM courses provides evidence:

that it is no longer appropriate to use lecture teaching as the comparison standard, and instead, research should compare different active learning methods, because there is such overwhelming evidence that the lecture is substantially less effective. (8320)

We must be careful to not jump to unrealistic conclusions and suggest that we stop lecturing all together. This isn’t reasonable because there are times when explaining concepts to students or sharing expertise is the most effective thing to do. There will always be a place for lecturing but the data is suggesting that the role should be diminished and greater emphasis should be placed on active learning activities.

For those who have been studying learning approaches these findings are not new. Active learning research has revealed that active learning approaches consistently provide better learner achievement than lecture only approaches. If we really want to be evidence-based then we need to stop comparing active learning approaches to the lecture and start exploring what active learning activities work best in what situations.

Determining what activities work best in what context is central to blended-learning. The reason well design blended learning is working is that most of the blended activities that get added to the learning environment have an active learning perspective. The key is the purposeful design of the learning environment starting with a clear overall course goal and well aligned outcomes, activities and assessments. All factors have to be taken into consideration and we must not loose site of the fact that our learner learn by doing.

References:

Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K., Okorafor, N., Jordt, H., and Wenderoth, M.P., (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 111 (23), 8410-8415.

Weiman, C.E., (2014. Large-scale comparison of science teaching methods sends clear message. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 111 (23), 8319-8320.

Source: https://www.travelers.com/iw-images/resources/Individuals/Large/DrivingInRainWind_large.jpg

Commuting in heavy rain is a normal part of living in North Vancouver and working in Burnaby. The other morning I was stuck behind a driver in a relatively new Mercedes who didn’t have enough confidence to drive past the rainy turbulence (wash) of an eighteen wheeled truck. Rather than deal with the spray or wash from the eighteen wheeler for a few seconds while passing the truck this driver chose to stay one lane over and beside the truck–in the truck’s blind spot and in the worst spray for way too long and too many kilometers. Not only was this dangerous for the driver of the Mercedes and the truck it put many other drivers at risk who were trapped behind these two vehicles. When the opportunity presented itself I managed to get around this dangerous blockage and noted that the Mercedes driver chose to stay in the truck’s wash and in the blind spot.

I acknowledge that driving past an eighteen wheeler in heavy rain can be somewhat unnerving. The truck sprays out so much water that your vehicle’s wipers become overloaded and you are almost driving blind for a second or two. You have to trust your driving ability and have enough confidence in your ability that you can maintain the right path past the truck. Once you push past the truck you only have to deal with the rain itself and can see a clear path ahead.

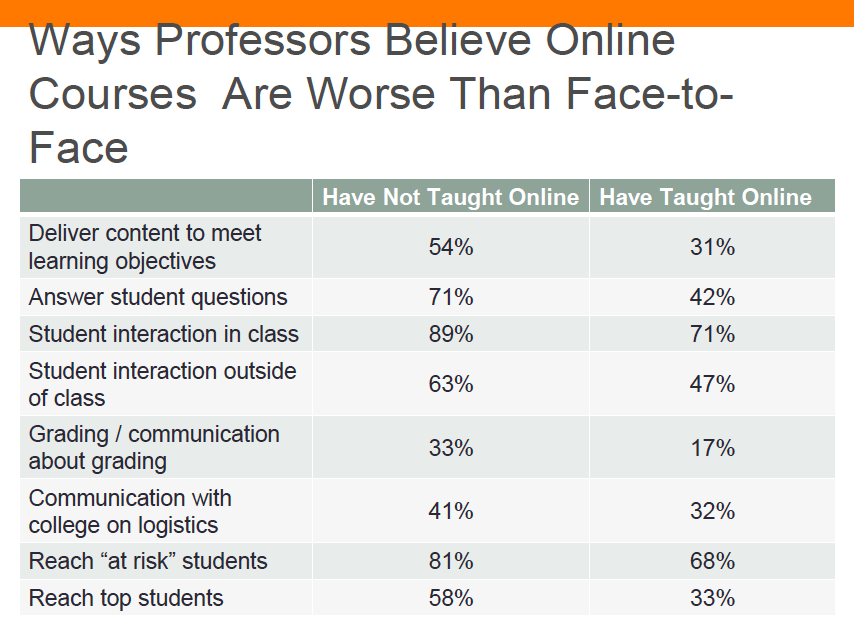

The fear of pushing past the wash from the truck reminds me of a situation that we are currently facing in Higher Education. The 2014 Inside Higher Ed/Gallup Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology reveals that despite the experimentation with online education many faculty fear that the record-high number of students taking those classes are receiving an inferior experience to what can be delivered in the classroom. Why? Whether faculty have experience in teaching online or have not taught online the majority of faculty believe that online classes are worse than face2face classes because they perceive student interaction inside class being much poorer online.

The above table points to several aspects of student to Professor interaction and vise versa that is perceived to be poorer online. To be fair to these Professors I think they are right. I have a suspicion that deep down they already know that since their primary form of instructional delivery in the face2face setting is the lecture, their level of interaction in traditional classes is already quite poor and if they carry this same type of interaction forward into the online realm they are right to worry that their online classes will be poorer.

Research conducted by Finkelstein, Seal, & Schuster revealed that 76% of the 172,000 faculty across North America surveyed use lecture as their primary instructional methodology. Lecturing is simply a passive form content delivery that all too often involves very little active student engagement. I will acknowledge that there are some exceptional Professors who have a high level of discussion in their classes and others who use active learning instructional methodologies but the data suggests that they are the minority. Additional research by Nunn in the form of monitoring Professors in their classes also revealed that at most three minutes out of a fifty minute class are actual discussion and most often in the form of questions at the end of class.

Unfortunately, many Professors initial experience with or understanding of online learning is that is it simply a way to use technology to deliver content. Whether content delivery is done face2face or online it is still the predominant form of instruction in the post secondary setting. Not enough Professors view learning as an active and dynamic process in which learners construct new ideas or concepts based upon their current/past knowledge. The making of meaningful connections is key to the learning and knowing and until we take the advice of people like Sir Ken Robinson and many other highly regarded educational experts and have a Learning Revolution, our current limited face2face information transfer model will simply be moved online.

So, since most Professors are involved in delivering content with very little interaction or engagement in the face2face setting is there any wonder why those Professors who haven’t taught online would see online courses as being even less effective? Similarly, since many Professors who move online continue to use content delivery as their primary form of instruction is there any wonder why these Professors also view online courses as further limiting their already limited face2face student engagement?

Until we can change the way that Professors view their role and move away from the passive information transfer model to an active and dynamic process in which learners construct their own knowledge; and until we can change the way the way most Professors view themselves as the “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side” or as a learning facilitators who create significant learning environments in which their students can come to know something, acquire knowledge, or to gain information and experience we can continue to expect to see these types of attitudes about online courses from faculty surveys.

This change of focus isn’t going to be easy. Due to a lack of formal training in active learning and all too often limited professional development many Professors are stuck in conducting their classes the same way that they experienced it when they were in school. This is very similar to the way that the Mercedes driver I referred to in my rain example was stuck in the wash behind the large truck–they didn’t have enough confidence in their own ability to push past the truck to see a clear path.

So once again it is not about the technology it is about the learning. Online technology is only a tool that can be used to enhance learning. But if our Professors are focused on teaching and disseminating information and not on creating significant learning environments then it doesn’t matter what tool we add to the mix, the student still loses out.

Finkelstein, M. J., Seal, R. K., and Schuster, J. The New Academic Generation: A Profession in Transformation. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Nunn, C. E. “Discussion in the College Classroom: Triangulating Observational and Survey Results.” Journal of Higher Education, 1996, 67 (3), 243-66.

Despite erroneously suggesting that MOOCs were invented in 2013 Anant Agarwal, the President of edX — Harvard’s and MIT’s collaborative MOOC venture and the instructor of the first edX course on circuits and electronics, points to some key aspects of the edX courses which contribute to student achievement. These include:

- Active Learning – Lessons are interleaved sequences of videos and interactive exercises.

- Self Pacing – Students can hit the pause button or even rewind the professor.

- Instant Feedback – Students can try to apply answers. If they get it wrong, they can get instant feedback. They can try it again and try it again until they great it right, and this really becomes much more engaging.

- Gamification – You can engage students much like they design with Legos…the learners are building a circuit with Lego-like ease. And this can also be graded by the computer.

- Peer Learning – Students answer each others questions in the online forums and the Prof confirms the right answer. Students are learning from each other and that they are learning by teaching.

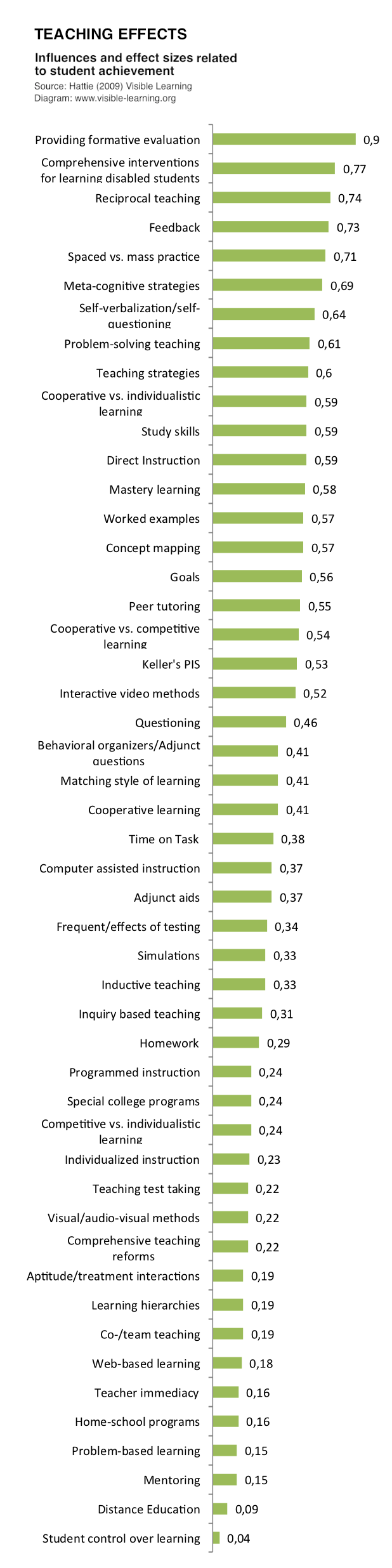

A well designed online course that provides the opportunity for active learning, self pacing, instant feedback and peer interaction can contribute toward student achievement and success. As we can see from John Hattie’s examples below of Teaching Effects several of the edX effects make the the top fo Hattie’s list:

Rather ask if online learning is working perhaps we should be asking if we are getting these same effects in our traditional classrooms.