Image source: http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/images/4/4c/IntroWordle.png

History of Learning Theories site highlighted in the video – https://kb.edu.hku.hk/learning_theory_history/

If you run a quick google search on the phrase “main learning theories” the results will reveal that there is inconsistency in what people agree are the main learning theories. You will also find that many sources will shift their perspectives on learning theories. For example back in 2016 when I first wrote this post, United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) which should be considered an authority listed the following 7 learning theories:

- Behaviorism

- Cognitive Psychology

- Constructivism

- Social Learning Theory

- Socio-constructivism

- Experiential Learning

- Multiple Intelligence

- Situated Learning and Community of Practice

- 21st Century Learning or Skills

When I updated this post in November of 2021 UNESCO revised their original list and now lists the Most influential theories of learning as:

- Behaviorism

- Cognitive Psychology

- Constructivism

- Social constructivism

- Experiential Learning

- Multiple Intelligence

- Situated Learning theory

- Community of Practice

While the changes are small, combining Social Learning Theory and Socio-Constructivism into what is now called Social Constructivism, lifting Situated learning to the level of a theory, removing 21st Century Learning or Skills and, moving Community of Practice into a separate category these changes reflect a shift from a contemporary or postmodern epistemological interpretation to a critical theory narrative.

Wikipedia points to Behaviourism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism as the main theories but also points to a wide assortment of related links. Learning-theories.com which was once a scholarly project but has now turned into an add riddled site suggests that there are the following 5 major paradigms which the different learning theories fall under:

- Behaviorism

- Cognitivism

- Constructivism

- Design-based

- Humanism

- 21st Century skills

Depending on the theoretical preference of the author(s) and when the site you land on was originally written or last updated you will find many of the theories from the lists above.

Back in the late 90’s when I was researching learning theories for my doctoral thesis and in 2003 when I taught my first graduate course on learning theories most texts and literature pointed to the following as the main theories:

- Behaviorism

- Cognitivism

- Humanism

Today the term Humanism is seldom used in the learning theory context and Constructivism has been pulled out of the Cognitive camp to stand on its own. Design is involved (or at least it should be) in most theories so I fail to see how this is a learning theory itself. Similarly, 21st Century learning is much more of a popular phrase of the day and since one could argue that all learning happening today is in the 21st Century, this really isn’t a learning theory.

Therefore, I suggest that the primary learning theories today are:

- Behaviorism

- Cognitivism

- Constructivism

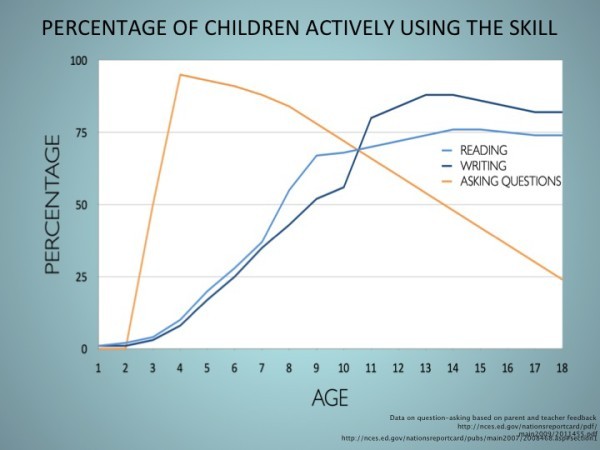

But which list is accurate? Perhaps a more important question is why is an understanding of learning theories important? The following four key points should serve as a good start for why understanding learning theories is so important:

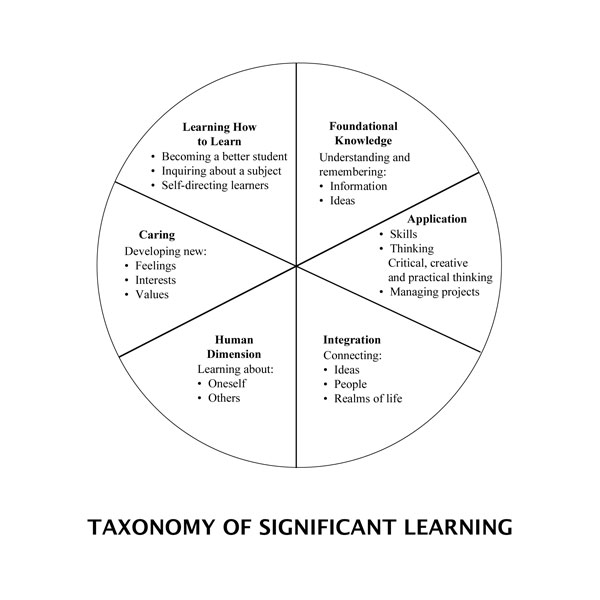

1. Knowing what you really believe about learning is important because this foundational belief should drive the way you create significant learning environments and the way you engage learners.

2. Knowing that your beliefs about learning are supported by evidence and are shared with others should give you the confidence to move away from the role of sage on the stage to guide on the side as you give your learners more choice, ownership, voice, and authenticity (COVA) in their learning experiences.

3. Knowing the full breadth of the learning theory or theories where your beliefs about learning fall will help you to analyze, assess, and choose the appropriate technologies that can not only fit the needs of your learners but enhance the learning environment.

If we don’t choose to take a proactive approach to understand what we fully believe about learning and purposefully design the learning environment, we choose to follow tradition. As Christopher Knapper warns there are consequences to blindly doing what has always been done:

…there is an impressive body of evidence on how teaching methods and curriculum design affect deep, autonomous, and reflective learning. Yet most faculty are largely ignorant of this scholarship, and instructional practices and curriculum planning are dominated by tradition rather than research evidence. As a result, teaching remains largely didactic, assessment of student work is often trivial, and curricula are more likely to emphasize content coverage than acquisition of lifelong and life-wide learning skills. (2010, p. 229)

Understanding what we believe about learning has never been more important. We are living in the age where we no longer are asking if we should use technology to enhance learning but are asking how well are we using technology to enhance learning. Tony Bates has spent decades researching how to use technology to enhance learning and in his post Learning theories and online learning he points to the fundamental role the understanding of theories of behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism play in online learning and more importantly reminds us that our thinking must continually evolve as these theories evolve. Bates also reminds us that we need to be open to new theories as these new and old learning theories evolve we must move from theory to practice. We need to be flexible enough to adapt and grow in our thinking about learning to develop effective learning environments that meet our learner’s needs.

This flexible and eclectic approach to understanding and adopting learning theories have driven my thinking about learning since the late 90’s when I developed Inquisitivism which is an approach for designing and delivering web-based instruction that shares many of the same principles of minimalism and other constructivist approaches. Being eclectic in my thinking about learning theories has enabled me to not limit my understanding of learning to one system but I have continually considered and selected the best elements from all systems.

Putting this in the 21st Century vernacular one could argue that I prefer the mashup theory of learning because creatively combining and mixing the best elements of learning theories is the best way to address the needs of 21st Century learners. Don’t assume that my mashup theory of learning is just a willy-nilly approach to being pragmatic. On the contrary, the quality of a mashup is totally dependent upon the quality of its components—remember I am continually selecting and mixing the best elements.

This finally takes me to my fourth key point why understanding learning theories is so important.

4. The better you know and understand specific learning theories the better able you will be to select the best elements from all the theories which will help you to mashup the most effective learning environment.

Regardless of where you land in your thinking about learning the fact that you are thinking about learning and how learning works means that your learners will benefit. When we strive to create significant learning environments we can all agree that it’s about the learning.

References

Knapper, C. (2010) ‘Changing Teaching Practice: Barriers and Strategies’ in Christensen Hughes, J. and Mighty, J. eds. Taking Stock: Research on Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Toronto ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press

Originally posted on March 11 and revised on November 10, 2021