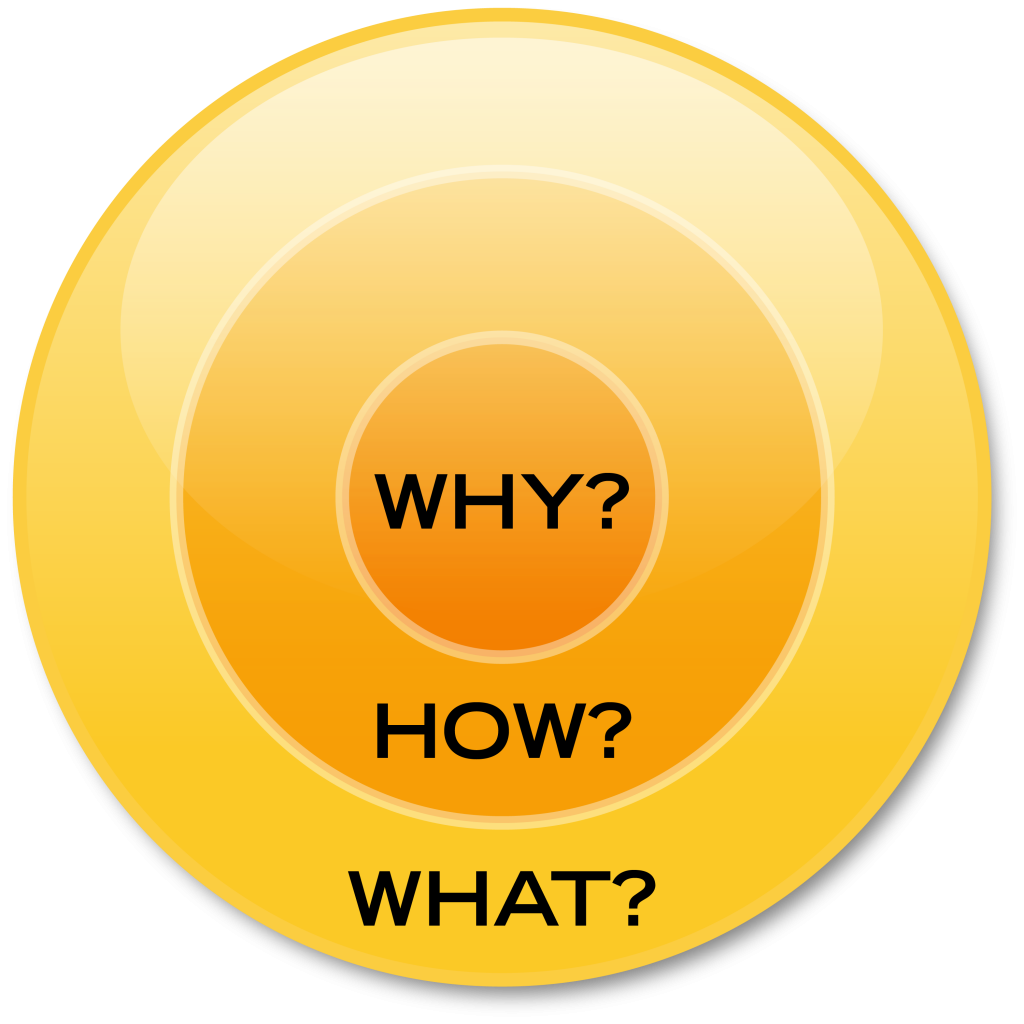

When a clear vision, what I will refer to as the “Why”, is missing people easily lose sight of their primary responsibility and get caught up in pushing priorities that may be important but when placed in context of the bigger picture result in a completely different focus. Let me explain…

My priority as an Instructional Development Consultant is to help faculty create the most effective learning environment. Therefore, I look for ways to use technology as a tool to enhance learning and create a more engaging environment. When I run into challenges, obstacles and the day to day bureaucracy of higher education I deal with those challenges or obstacles in such a way that they don’t hinder the faculty from creating significant learning environments and look for ways to ensure that we are still effectively serving our learner.

In contrast, if a person doesn’t have a clear understanding of Why we do what we do then they are left to focus on their own priorities and that usually means getting caught up in the details and minutia of their job. Institutions like BCIT have a FOIPOP policy and generally the purpose of these types of policies are to:

– Ensure compliance with the Freedom of Information and Protection and Privacy Act

– Define the roles of employees and contractors in complying with the Act

– Reduce the institutions liability and risk of litigation due to inappropriate handling of information

– Protect the institutions reputation

These are all admirably and necessary purposes and it is good that we have a policy and office which is concerned with these issues. Depending on your Why, something like a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FOIPOP) can be dealt with in two different ways.

First way

Without a bigger Why the people tasked with ensuring that these purposes are upheld make these purposes the top priority and all activities are weighed against these priorities. The best example of this in higher education is the debate of using the cloud, social media and other collaborative and distributed resources which the institution does not control. If a person’s Why is to enforce the policy then free software that is based in the cloud, social media tools and other resources cannot be used because these tools contravene the policy. If people are adamant about using these tools then explicit hoops must be jumped through or the institution will create its own cloud based tools that they can control. The first and most common response is to abstain or restrict for fear of the consequences. Fear becomes the driving force. Fear is the factor that is preventing all of higher education from moving to Google Docs or Office 365 and providing their students access to the most widely used collaborative tool, not to mention saving millions of dollars each year.

Second way

In contrast, if an institution and all members hold that their Why is much bigger than a policy and the top priority is to create the most effective learning environment for its students, when they come up against a policy like FOIPOP the response will not be reactive and based on fear. It will be proactive and creativity will be used to explore how can we use these engaging collaborative tools and still adhere responsibility to FOIPOP. With the right Why, people are automatically looking for ways to use these tools and still satisfy the FOIPOP requirements. More importantly the right Why can motivate people to explore creative solutions like revisiting the legislation to see if the interpretation that is being made is really the best interpretation that will help us to insure that we are creating significant learning environments.

IF everyone in an organization from the housekeeping staff on up to the President all hold the same Why—something like:

We are committed to creating significant learning environments that will help prepare our learners to face an uncertain future and enable them to learn how to learn and ultimately solve problems that don’t even exist.

then FOIPOP and other bureaucratic obstacles are not dealt with reactively in fear but are proactively managed in such a way that they do not hinder the bigger Why.

The change of perspective that a clearly defined and well communicated Why can move an organization from being fearful and reactive to being creative and proactive, assuming an organization has the leadership wisdom to value proactive workers (see my post The Paradox of Being Proactive.

Does your institutions have a clear and well communicated Why? If it doesn’t what can you do about it?